Click on an image to view

full-sized

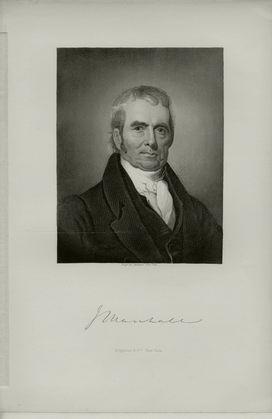

Marshall, John, jurist,

born in Germantown, Fauquier County, Virginia, 24 September, 1755;

died in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 6 July, 1835, received from

childhood a thorough course of domestic education in English

literature, and when he was sufficiently advanced his father

procured the services of a private teacher, Reverend James Thompson,

an Episcopal clergyman from Scotland, who was afterward minister of

Leeds parish. At fourteen years of age John was sent to Westmoreland

county, and placed at the school where his father and Washington had

been pupils. James Monroe was one of his fellow-students. After

remaining there for a year he returned to Oak Hill and continued his

classical studies under the direction of Mr. Thompson, but he never

had the benefit of a college education.

He began the study of law at the age of eighteen, and used

Blackstone's "Commentaries," then recently published, but he

had hardly begun his legal studies when the controversy with the

mother country came to a crisis. The tea bill, the Boston port bill,

the congress of 1774, followed one another in quick succession, and

every question at issue was thoroughly discussed at Oak Hill just at

the period of young Marshall's life to make the most indelible

impression upon his intellectual and moral character. Military

preparations were not neglected. John Marshall joined an independent

body of volunteers and devoted himself with much zeal to the

training of a company of militia in his neighborhood. Among the

first to take the field was Thomas Marshall.

A regiment of minutemen was raised in the summer of 1775 in

Culpeper, Orange, and Fauquier counties, of which he was appointed

major, and his son , John a lieutenant. On their green

hunting-shirts they bore the motto "Liberty or death !" and

on their banner was the emblem of a coiled rattlesnake, with the

inscription "Don't tread on me!" They were armed with rifles,

knives, and tomahawks. They had an engagement with Governor

Dunmore's forces at Great Bridge on 9 December, in which Lieutenant

Marshall showed coolness and skill in handling his men.

After this, in 1776, the father and son were in separate

organizations. Thomas Marshall was appointed colonel in the 3d

Virginia infantry of the Continental line, and John's company was

reorganized and attached to the 11th regiment of Virginia troops,

which was sent to join Washington's army in New Jersey. Both were in

most of the principal battles of the war until the end of 1779. John

was promoted to a captaincy in May, 1779. His company distinguished

itself at the battle of the Brandywine. He was engaged in the

pursuit of the British and the subsequent retreat at Germantown, was

with the army in winter-quarters at Valley Forge, and took part in

the actions at Monmouth, Stony Point, and Paulus Hook. His marked

good sense and discretion and his general popularity often led to

his being selected to settle disputes between his brother officers,

and he was frequently employed to act as deputy judge-advocate. This

brought him into extensive acquaintance with the officers, and into

personal intercourse with General

Washington and Colonel Alexander

Hamilton, an acquaintance that subsequently ripened into sincere

regard and attachment The term of enlistment of his regiment having

expired, Captain Marshall, with other supernumerary officers, was

ordered to Virginia to take charge of any new troops that might be

raised by the state, and while he was detained in Richmond during

the winter of 1779-'80, awaiting the action of the legislature, he

availed himself of the opportunity to attend the law lectures of

George Wythe, of William and Mary college, and those of Professor

(afterward Bishop) Madison on natural philosophy.

In the summer of 1780 Marshall received a license to practice

law, but, on the invasion of Virginia by General Alexander Leslie in

October, he joined the army again under Baron Steuben, and remained

in the service until Arnold,

after his raid on James river, had retired to Portsmouth. This was

in January, 1781. He then resigned his commission, and studied law

He had spent nearly six years in arduous military service, exposed

to the dangers, enduring the hardships, and partaking the anxieties

of that trying period. The discipline of those six years could not

have failed to strengthen the manliness of his character and greatly

enlarge his knowledge of the chief men, or those who became such,

from every part of the country, and of their social and political

principles. Though it was a rough and severe school, it was

instructive, and produced a maturity and self-dependence that could

not have been acquired by a much longer experience under different

circumstances.

As soon as the courts were re-opened young Marshall began

practice, and quickly rose to high distinction at the bar. In the

spring of 1782 he was elected to the house of burgesses, and in the

autumn a member of the state executive council. On 3 January. 1783,

he married Mary Willis Ambler, daughter of the state treasurer, with

whom he lived for nearly fifty years, and about the same time he

took up his permanent residence in Richmond. In the spring of 1784

he resigned his seat at the council board in order to devote himself

more exclusively to his profession, but he was immediately returned

to the legislature by Fauquier county, though he retained only a

nominal residence there. In 1787 he was elected to represent

Henrico, which includes the city of Richmond. He was a decided

advocate of the new United States constitution, and in 1788 was

elected to the state convention that was called to consider its

ratification. His own constituents were opposed to its provisions,

but chose him in spite of his refusal to pledge himself to vote

against its adoption. In this body he spoke only on important

questions, such as the direct power of taxation, the control of the

militia, and the judicial power--the most important features of the

proposed government, the absence of which in the Confederation was

the principal cause of its failure. On these occasions he generally

answered Patrick

Henry, the most powerful opponent of the constitution, and he

spoke with such force of argument and breadth of views as greatly to

affect the final result. which was a majority in favor of

ratification.

The acceptance of the constitution by Virginia was entirely due

to the arguments of Marshall and James

Madison in the convention which recorded eighty-nine votes for

its adoption against seventy-nine contrary voices. When the

constitution went into effect, Marshall acted with the party that

desired to give it fair scope and to see it fully carried out. His

great powers were frequently called into requisition in support of

the Federal cause, and in defense of the measures of Washington's

administration.

His practice, in the mean time, became extended and lucrative. He

was employed in nearly every important cause that came up in the

state and United States courts in Virginia. In addition to these

labors, he served in the legislature for the two terms that followed

the ratification of the constitution, contemporary with the sittings

of the first congress under it, when those important measures were

adopted by which the government was organized and its system of

finance was established, all of which were earnestly discussed in

the house of burgesses. He also served in the legislatures of 1795

and 1796, when the controversies that arose upon Jay's treaty and

the French revolution were exciting the country. At this post he was

the constant and powerful advocate of Washington's administration

and the measures of the government. The treaty was assailed as

unconstitutionally interfering with the power of congress to

regulate commerce; but Marshall, in a speech of remarkable power,

demonstrated the utter fallacy of this argument, and it was finally

abandoned by the opponents of the treaty, who carried a resolution

simply declaring the treaty to be inexpedient.

In August, 1795, Washington offered him the place of

attorney-general, which had been made vacant by the death of William

Bradford, but he felt obliged to decline it. In February, 1796,

he attended the supreme court at Philadelphia to argue the great

case of the British debts, Ware vs. Hylton, and while he was

there received unusual attention from the leaders of the Federalist

party in congress. He was now, at forty-one years of age,

undoubtedly at the head of the Virginia bar; and in the branches of

international and public law, which, from the character of his cases

and his own inclination, he had profoundly studied, he probably had

no superior, if he had an equal, in the country.

In the summer of 1796 Washington tendered him the place of envoy

to France to succeed James

Monroe, but he declined it, and General Charles C. Pinckney was

appointed. As the French Directory refused to receive Mr. Pinckney,

and ordered him to leave the country, no other representative was

sent to France until John Adams became president. In June, 1797, Mr.

Adams appointed Messrs. Pinckney, Marshall, and Elbridge Gerry as

joint envoys. Marshall's appointment was received with great

demonstrations of satisfaction at Richmond, and on setting out for

Philadelphia he was escorted several miles out of the city by a body

of light horse, and his departure was signalized by the discharge of

cannon. The new envoys were as unsuccessful in establishing

diplomatic relations with the French republic as General Pinckney

had been. They arrived at Paris in October, 1797, and communicated

with Talleyrand, the minister for foreign affairs, but were cajoled

and trifled with. Secret agents of the minister approached them with

a demand for money--50,000 pounds sterling for private account, and

a loan to the government. Repelling" these shameful suggestions with

indignation, the envoys sent Talleyrand an elaborate paper, prepared

by Marshall, which set forth with great precision and force of

argument the views and requirements of the United States, and their

earnest desire for maintaining friendly relations with France. But

it availed nothing. Pinckney and Marshall, who were Federalists,

were ordered to leave the territories of the republic, while Gerry,

as a Republican, was allowed to remain. The news of these events was

received in this country with the deepest indignation. "History

will scarcely furnish the example of a nation, not absolutely

degraded, which has experienced from a foreign power such open

contumely and undisguised insult as were on this occasion suffered

by the United States. in the persons of their ministers," wrote

Marshall afterward in his " Life of Washington."

Marshall returned to the United States in June, 1798, and was

everywhere received with demonstrations of the highest respect and

approval. At a public dinner given to him in Philadelphia, one of

the toasts was "Millions for defence; not a cent for

tribute," which sentiment was echoed and re-echoed throughout

the country. Patrick Henry wrote to a friend:" Tell Marshall I

love him because he felt and acted as a republican, as an

American." In August Mr. Adams offered him a seat on the supreme

bench, which had been made vacant by the death of Judge James

Wilson, but he declined it, and his friend, Bushrod Washington, was

appointed. In his letter to the secretary of state, declaring his

intention to nominate Marshall, President Adams said: "Of the

three envoys the conduct of Marshall alone has been entirely

satisfactory, and ought to be marked by the most decided approbation

of the public. He has raised the American people in their own

esteem, and if the influence of truth and justice, reason and

argument, is not lost in Europe, he has raised the consideration of

the United States in that quarter of the world."

As the elections approached, Mr. Marshall was strongly urged to

become a candidate for congress, consented much against his

inclination, was elected in April, 1799, and served a single

session. One of the most determined assaults that was made against

the administration at this session was in relation to the case of

Jonathan Robbins, alias Thomas Nash, who had been arrested in

Charleston at the instance of the British consul, on the charge of

mutiny and murder on the British frigate "Hermione," and who, upon

habeas corpus, was delivered up to the British authorities by Judge

Thomas Bee, in pursuance of the requisition of the British minister

upon the president, and of a letter from the secretary of state to

Judge Bee advising and requesting the delivery. Resolutions

censuring the president and Judge Bee were offered in the house; but

Marshall, in a most elaborate and powerful speech, triumphantly

refuted all the charges and assumptions of law on which the

resolutions were based, and they were lost by a decided vote. This

speech settled the principles that have since guided the government

and the courts of the United States in extradition cases, and is

still regarded as an authoritative exposition of international law

on the subject of which it treats. The session lasted till 14 May,

but on the 7th Marshall was nominated as secretary of war in place

of James McHenry, who had resigned ; and before confirmation, oil

the 12th, he was nominated and appointed secretary of state in place

of Timothy Pickering, who had been removed.

He filled this office with ability and credit during the

remainder of Adams's administration. His state papers are luminous

and unanswerable, especially his instructions to Rufus King,

minister to Great Britain. in relation to the right of search, and

other difficulties with that country Chief-Justice Ellsworth having

resigned his seat on the bench in November, 1800, the president,

after offering the place to John

Jay, who declined it, conferred the appointment on Mr. Marshall.

The tradition is, that after the president had had the matter under

consideration for some time, Mr. Marshall (or General Marshall, as

he was then called) happened one day to suggest a new name for the

place, when Mr. Adams promptly said: "General Marshall, you need

not give yourself any further trouble about that matter. I have made

up my mind about it." "I am happy to hear that you are relieved on

the subject," said Marshall. "May I ask whom you have fixed

upon? .... Certainly," said the president ; "I have concluded

to nominate a person whom it may surprise you to hear mentioned. It

is a Virginia lawyer, a plain man by the name of John Marshall."

He was nominated on 20 January, unanimously confirmed, and

presided in the court at the February term, though he was still

holding the office of secretary of state. He at once took, and

always maintained, a commanding position in the court, not only as

its nominal but as its real head. The most important opinions,

especially those on constitutional law, were pronounced by him. The

thirty volumes of reports, from 1st Cranch to 9th Peters, covering a

period of thirty-five years, contain the monuments of his great

judicial power and learning, which are referred to as the standard

authority on constitutional questions. They have imparted life and

vigor not only to the constitution, but to the national body

politic. It is not too much to say that for this office no other man

could have been selected who was equally fitted for the task he had

before him. To specify and characterize the great opinions that he

delivered would be to write a treatise on American constitutional

law. They must themselves stand as the monuments and proper records

of his judicial history. It is reported by one of his descendants

that he often said that if he was worthy of remembrance his best

biography would be found in his decisions in the supreme court.

Their most striking characteristics are crystalline clearness of

thought, irrefragable logic, and a wide and statesman-like view of

all questions of public consequence.

In these respects he has had no superior in this or any other

country. Some men seem to be constituted by nature to be masters of

judicial analysis and insight. Such were Papinian, Sir Matthew Hale,

and Lord Mansfield, each in his particular province. Such was

Marshall in his. They seemed to handle judicial questions as the

great Euler did mathematical ones, with giant ease. As an instance

of the simplicity with which he sometimes treated great questions

may be cited his reasoning on the power of the court to decide upon

the constitutionality of acts of congress. It had been claimed

before; but it was Marshall's iron logic that settled it beyond

controversy. " It is a proposition too plain to be contested,"

said he, in Marbury vs. Madison, "that the

constitution controls any legislative act repugnant to it; or that

the legislature may alter the constitution by an ordinary act.

Between these alternatives there is no middle ground. The

constitution is either a superior, paramount law, unchangeable by

ordinary means, or it is on a level with ordinary legislative acts,

and, like other acts, is alterable when the legislature shall please

to alter it. If the former part of the alternative be true, then a

legislative act contrary to the constitution is not law; if the

latter part be true, then written constitutions are absurd attempts,

on the part of the people, to limit a power in its own nature

illimitable."

The incidents of Marshall's life, aside from his judicial work,

after he went upon the bench, are few. In 1807 he presided, with

Judge Cyrus

Griffin, at the great state trial of Aaron

Burr, who was charged with treason and misdemeanor. Few public

trials have excited greater interest than this. President

Jefferson and his adherents desired Burr's conviction, but

Marshall preserved the most rigid impartiality and exact justice

throughout the trial, acquitting himself, as always, to the public

satisfaction.

In 1829 he was elected a delegate to the convention for revising

the state constitution of Virginia, where he again met Madison and

Monroe, who were also members, but much enfeebled by age. The chief

justice did not speak often, but when he did speak, though he was

seventy-four years of age, his mind was as clear and his reasoning

as solid as in younger days. His deepest interest was excited in

reference to the independence of the judiciary. He remained six

years after this on the bench of the supreme court. In the spring of

1835 he was advised to go to Philadelphia for medical advice, and

did so, but without any beneficial result, and died in that city.

In private Chief-Justice Marshall was a man of unassuming piety

and amiability of temper. He was tall, plain in dress, and somewhat

awkward in appearance, but had a keen black eye, and overflowed with

geniality and kind feeling. He was the object of the warmest love

and veneration of all his children and grandchildren. Judge Marshall

published, at the request of the first president's family, who

placed their records and private papers at his disposal, a "Life

of Washington" (5 vols., Philadelphia, 1804-'7), of which the

first volume was afterward issued separately as "A History of the

American Colonies" (1824). The whole was subsequently revised

and condensed (2 vols., 1832), in this work he defended the policy

of Washington's administration against the arguments and detractions

of the Republicans. A selection from his decisions has been

published, entitled "The Writings of John Marshall, late Chief

Justice of the United States, upon the Federal Constitution"

(Boston, 1839), under the supervision of Justice Joseph Story.

His life has been written by George Van Santvoord, in his

"Sketches of the Chief Justices" (New York, 1854); and by

Henry Flanders, in his "Lives and Times of the Chief Justices"

(2d series, Philadelphia, 1858). See also "Eulogy on the Life

and Character of Marshall," by Horace Binney (Philadelphia,

1835); "Discourse upon the Life, Character, and Services of John

Marshall," in Joseph Story's " Miscellaneous Writings" (Boston,

1852); "Chief-Justice Marshall and the Constitutional Law of his

Time," an address by Edward J. Phelps (1879); and "John

Marshall," by Allan B. Magruder (Boston, 1885).

MARSHALL, Thomas, planter father of John Marshall, born in

Virginia about 1655; died in Westmoreland county, Virginia, in 1704.

His father, John, a captain of cavalry in the service of Charles I.,

emigrated to Virginia about 1650. He owned a large plantation in

Virginia, and was the head of the Marshall family of Virginia and

Kentucky.--His grandson, Thomas, born in Washington parish,

Westmoreland County, Virginia, 2 April, 1730: died in Mason county,

Kentucky, 22 June, 1802, was the son of "John of the Forest," so

called from the estate that he owned, was educated in Reverend

Archibald Campbell's school, and subsequently assisted Washington in

his surveying excursions for Lord Fairfax and others, for which he

received several thousand acres of land in West Virginia. He was a

lieutenant of Virginians in the French and Indian war, and

participated in the expedition of General Braddock against Fort

Duquesne, but, having been detailed as one of the garrison at Fort

Necessity, was not at the defeat. In 1753 he accepted the agency of

Lord Pairfax to superintend a portion of his estate in the "Northern

neck," and in 1754 married Mary Randolph, daughter of Reverend James

Keith, an Episcopal clergyman of Pauquier. In 1765 he removed to

Goose Creek, and in 1773 purchased "The Oaks" or" Oak Hill" in Leeds

parish in the northern part of Fauquier county. In 1767 he was high

sheriff of Fauquier county, and he was frequently a member of the

house of burgesses. He condemned and pledged resistance to the

encroachments of the crown, and was a member of the Virginia

convention that declared her independence. In 1775, on the summons

of Patrick Henry, he recruited a battalion and became major of a

regiment known as the "Culpepper minute-men." He afterward became

colonel of the 3d Virginia regiment. At the battle of Brandywine his

command was placed in a wood on the right, and, though attacked by

greatly superior numbers, maintained its position without losing an

inch of ground until its ammunition was nearly expended and more

than half its officers and .one third of the soldiers were killed or

wounded. The safety of the patriot army on this occasion was largely

due to the good conduct of Colonel Marshall and his command. The

house of burgesses voted him a sword. At Germantown his regiment

covered the retreat of the patriot army. He was with Washington at

Valley Forge. He was afterward ordered to the south, and was

surrendered by General Lincoln at Charleston in 1780. When paroled

he took advantage of the circumstance to make his first visit to

Kentucky on horseback over the mountains, and then located the lands

on which he subsequently lived in Wood-ford, having been exchanged,

he resumed his command and held it until the close of the war. In

1781 he was for a time in command at York. He was appointed

surveyor-general of the lands in Kentucky in 1783, in that year

established his office in Lexington, and removed his family to

Kentucky in 1785. In 1787 and 1788 he represented Fayette county in

the Virginia assembly. In the latter year he was also a delegate to

the convention in Danville to consider the separation of Kentucky

from Virginia. He was appointed by Washington collector of revenue

for Kentucky. He and all his family were Federalists.